The term “pragmatism” is arguably one of the most misunderstood terms/ideas today. The street meaning is “do whatever works – whatever it takes.” Or a more precise version: “action unencumbered by principle.” When we approach a decision we often say things like: “don’t overthink it; keep it simple; this isn’t brain surgery; ready-shoot-aim; if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it; if it ain’t broke, break it; etc. etc.” We are all practical which we equate with pragmatic. Many business people see being “pragmatic” as the antithesis of being “philosophical”. Just the opposite!

Since Pragmatism, America’s only unique contribution to the long history of Philosophy in the West, and, while a true innovation, it is well to remember James’s titled his 1906 Lowell Lectures: “Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking.” Peirce in his 1903 Harvard lectures proclaimed: Pragmatism as a Principle and Method for Right Thinking.

Here are some of the leading Classical American Pragmatists, the subject of Nahser’s dissertation in moral philosophy – relevant chapters 5 and 6: “Learning to Read the Signs: Reclaiming Pragmatism for the Practice of Sustainable Management.” (See also left panel.)

The Founders of Pragmatism– Classical American Philosophy .

While there are more members of the so-called Classical American Philosophers, six of the best-known are Charles Sanders Peirce, Josiah Royce, William James, Mary Parker Follett, and John Dewey and Jane Addams. They all knew each other. Peirce and James grew up and studied together at Harvard. James and Royce were on the Harvard Philosophy faculty together for several decades. Follett studied with Royce and James. Dewey had studied with Peirce during his brief academic teaching at Johns Hopkins. And then Dewey worked extensively with Jane Addams at Hull House. (See upper right panel.)

While not on the usual list, we feature Mary Parker Follett who became the first person to apply pragmatism to organization management. Therefore, we consider her the “Founder of Pragmatic Management” (see below.)

Alfred North Whitehead joined the tradition in 1924 with his appointment to the Harvard Philosophy Department.

Charles Sanders Peirce

1839 –1914

Charles Sanders Peirce today is widely recognized by philosophers – but still little-known publicly – as the most profound and original philosopher America has produced. He is credited with introducing the formulation of pragmatism (and semiotics) as a philosophy; America’s only unique contribution to the history of Philosophy. James popularized it, and Dewey wrote extensively about its application in education. Peirce stated that every inquiry must begin with a doubt (what he called a stance of “fallibilism”) and that the meaning of an idea is expressed in the consequences of that idea – quoting the biblical “by their fruits you shall know them.”

Peirce stated it formally: “Consider what effects, which might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of those effects is the whole of our conception of the object.” This definition became famously known as “The Pragmatic Maxim.

While a scientist, he challenged the prevailing “Gospel of Greed” of the day which he saw resulting from a narrow interpretation of Darwin’s “survival of the fittest.” His answer was “Evolutionary Love” – his landmark 1893 The Monist essay – gained from his deeply felt insight that we engage in forming community and caring for one another as one of the three drivers of evolution; the other two being chance and necessity.

He famously said, watching how the debate over his pragmatic philosophy and writings raged, that he would rename his philosophy “pragmaticism” a name he said was ““ugly enough to be safe from kidnappers.” We are still attempting to reclaim the original meaning of pragmatism…still not safe from misappropriation: “do whatever works.” Ouch!

It has been said that Peirce has the distinction of having fewer disciples at death than any other world class philosopher in western history – 4 by actual count. Luckily for Peirce, one of them was William James. Josiah Royce and John Dewey were two others, mentioned below.

William James

1842 –1910

James Introduced the term “pragmatism” to the world in a lecture at UC Berkeley in 1898 entitled, fittingly “Philosophical Conceptions and Practical Results.” That is when he stated the much misunderstood definition of Pragmatism: you know an idea by its “cash value.” ” The ultimate test for us of what the truth means Is Indeed the conduct it dictates or Inspires.” True, but it too often has come to mean: “Do whatever works.” A far cry from the original intent of testing/putting values in action.

We all should have the courage to follow his practice:

“On the principle of going behind the conceptual function altogether, however, and looking into more primitive flux of the sensational life for reality’s true shape, a way is open to us...Plunge into an altogether other dimension of existence from the sensible and merely ‘understandable’ world. The unseen region in question is not merely ideal, for it produces effects in this world...Truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made true by events.“

Josiah Royce

1855-1916

Josiah Royce was one of the few people in Peirce’s lifetime whom he felt really understood what he meant by pragmatism. Indeed Peirce went so far as to call Royce the only true American pragmatist. Like James, Royce was interested in the pursuit of truth but unlike James he did not just look at what “worked” but how we formed our ideas to begin with. Royce wanted answers to questions about purpose, duty, and goals. So he posed questions like: what do we live for? What is the ideal of life? His focus on duty led him to thinking about the virtue of loyalty and this led into the central question of the formation of the Christian community which he called the “Beloved Community”. Since he saw all philosophy as the process of interpretation, he used the example of the early Christian community attempting to interpret the meaning Jesus’s life, which led to the formation of the “Beloved Community.”

Royce believed that “Every proposed reform, every moral deed, is to be tested by whether and to what extent it contributes to the realization of the Beloved Community…When one cannot find the ‘beloved community,’ she needs to take steps to create it and if there is not evidence of the existence of such a community then the rule to live by is: To Act So As To Hasten Its Coming.”

Mary Parker Follett

1868-1933

The most important person on this “History of Pragmatism” page, for our purposes, is Mary Parker Follett for the simple reason that she was the first to connect the practice of pragmatism to the practice of management. It was her work in community development focused on group dynamics and vocational training that brought her to the attention of manufacturers in America and England. (She was one of the first women to lecture at the London School of Economics.)

After her death, she joined what has been regrettably called “the invisible women in the history of American Philosophy.” But her ideas of management are being recovered today by leaders of management theory who are often astounded to read her work and find themselves merely repeating what she said. The late Warren Bennis, one of the deans of the “Human Relations” movement, remarked in 2003 that “Just about everything written today about leadership and organizations comes from Mary Parker Follett’s writings and lectures.” Like her familiar definition of management as “the art of getting things done through people.”

For example, Bennis: “Leaders are people that can express themselves fully.” Follett: : “A leader is a person who expresses most fully the spirit of the age, large understanding, clear vision and steadiness of purpose.” (We like her definition!)

Feminist pragmatists (e.g. see right side panel on this page) find connections with pragmatic philosophy throughout Follett’s work, particularly on inclusive groups, integrative inquiry, and the importance of focusing on the “job” and its context as a deeply relational activity. She saw life as a “ceaseless interweaving; ideas and experiences are woven into the tissue of my life.” “We verified through the process of creating.” Her commitment was to “progressive integrations,” continually creating the person and society.

This belief that ideas and situations “become true” follows James and Royce whom she studied with at “Harvard Annex” – Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women. Harvard later recognized the Annex as Radcliffe College from which she belatedly earned a degree – summa cum laude…after 9 years of intermittent study, including one year at Newnham College in Cambridge, England. (Her work by today’s standards would easily have earned a PhD.)

Quoting James, she said he “tried to show us the relation between what he called the inmost nature of reality and our own powers…my capacities are related to the demands of the universe. I believe that the great leader can show me this correspondence that can quicken and give direction to some force within me…whoever connects me with the hidden springs of all life, whoever increases the sense of life in me, he is my leader.” (We often refer this as a “calling.” See Presidio Graduate School story.)

One of her major efforts was to have business management seen as a profession with a foundation of science and a motive of service for the “general social good.” “Do you not think that the recognition of organization as the chief need of business is rather interesting when we remember that conscious organization is the great spiritual task of man?” In this work, like a craftsman, we should ask the question: “How can I make of my life a whole whose beauty and use shall be one?”

She recognized that business needed to make a profit and saw nothing wrong with that. But only that it should be seen as one of many motives : “We all want the richness of life in terms of our deepest desire. We can purify and elevate our desires, we can add to them, but there is no individual or social progress in curtailment of desires.”

This practice of management is diametrically opposed to the reductionist, hierarchical, job efficiency management focus of Frederick Winslow Taylor, founder of “Scientific Management.” His book with that title was voted in 2001 as the most influential management book of the 20th century by the fellows of the Academy of Management.

How different our practice of management would be if Dynamic Administration – the Collected Papers of Mary Parker Follett had been the most influential book…but there is still time and overwhelming need today to connect with the “hidden springs of all life” she experienced and described, so that all life may flourish.

John Dewey

1859 –1952

John Dewey had the most impact in his writings on education. In the book for school teachers How We Think, he attempted to bring together reflective thought with objective inquiry. (It was the only book he revised – 15 years later after thousands of teachers had tested his educational philosophy.) He noted the importance of the continuum of inquiry: “…a principle whose importance, as far as I am aware, only Peirce had previously noted.”

That led to the succinct summary that education is “the continuous reconstruction of experience.”

When asked what thinkers had an influence on him he replied: “I should state explicitly that, with the outstanding exception of Peirce, I’ve learned most from writers with whose position I have in the end been compelled to disagree.”

The rich story of the development of pragmatic inquiry goes on today

where of particular note are feminist philosophers who are embracing

the collective/community nature of inquiry stressed by the early

pragmatists and by Follett (above). Dewey concurred: “neglect of context is the greatest single disaster which philosophic thinking can incur. (See bibliography for further readings.) We turn below to the predecessors, since ideas, as Dewey stated, come from a continuum of inquiry. What Jefferson called “the expression of the American mind,” see below.

Alfred North Whitehead

1861-1947

Whitehead, while from England, is considered one of the Classical American Pragmatists because, during his years at Harvard, he produced his most important philosophical works, and these included his works on education, specifically business education. He formed a close friendship with the legendary Harvard Business School dean, Wallace Donham. Whitehead adapted his HBS lecture “On Foresight” as the preface to Donham’s 1931 book provocatively titled Business Adrift.

in his HBS lecture, Whitehead stated the task management education: “The behavior of the community is largely dominated by the business mind. A great society is a society in which its men (and women) of business think greatly of their functions…There can be no successful democratic society until general education conveys a philosophic outlook…Philosophy is an attempt to clarify those fundamental beliefs which finally determined the emphasis of attention that lies at the base of character. “

He concludes: “There is now no choice before us: either we succeed in providing a rational coordination of impulses and thoughts, or for centuries civilization will sink into a mere welter of minor excitements. We must produce a great age, or see the collapse of the upward striving of our race.” Challenging words for us all to help implement this philosophical education for the economic mind to “think greatly of their function” and create a just and sustainable world.

Predecessors to the American Pragmatists

Note: This section is a work in progress to show the unique American Experience with Pragmatic Practice; demonstrations of the American “Arc of Pragmatic Inquiry” at work at key moments in our history: Although not named as pragmatists, Thomas Jefferson, Alexis de Tocqueville, Abraham Lincoln, Frances E. Willard, Jane Addams and Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalists show the practice of pragmatism leading to Peirce, et.al. to articulate it.

Thomas Jefferson

1743-1826 (July 4)

The Declaration of Independence of course is famous as the statement of modern democracy. It is also important to us as a statement of American thinking. Jefferson stated later in life: “Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, not yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind.”

And we are claiming that the American mind at its best thinks pragmatically. Specifically, the meaning of “pursuit of happiness” which is often overlooked as idealistic, but had precise meaning for Jefferson: happiness serving others, drawn from the Scottish Enlightenment and his teacher at William & Mary, William Small. See: Declaration of Independence as a Pragmatic Statement. And a longer video story: Thomas Jefferson’s Education as a Pragmatist.

Alexis de Tocqueville

1805-1859

de Tocqueville’s visit to America was published as the landmark Democracy in America in 1835, after extensive travels throughout the eastern United States. He observed what he called our “habits of the heart” and was one of the first to bring the idea and language of “individualism” to this country.

He begins Vol. II, Part I, Chapter 1 entitled “Concerning the Philosophical Approach of the Americans” with this opening sentence: “Less attention, I suppose, is paid to philosophy in the United States than in any other country in the civilized world… I should say that in most mental operations, each American relies on individual effort and judgment. So in all the countries of the world, America is the one in which the precepts of Descartes are least studied and best applied.” (This is referencing Descartes’s famous internal mental quest for certainty: Cogito Ergo Sum: “I think, therefore I am.”)

However, he went on to observe: “Americans of all ages, all stations in life, and all types of dispositions are forever forming associations,” Combining these two deep beliefs of individual freedom and the impulse to form communities is exactly what Jefferson intended the immortal words of the Declaration of Independence: …life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness – by which he meant serving in the community life. (See “Thomas Jefferson’s Education as a Pragmatist.” referenced above.) That is our hope: forming into corporate bodies to serve the Common Good.

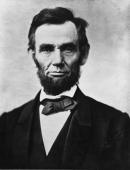

Abraham Lincoln

1809-1865

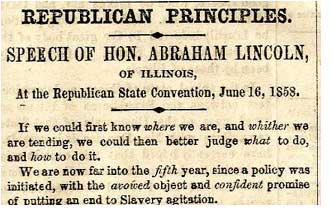

“If we could first know where we are and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it. “A House Divided” June 16, 1858.

One of the major challenges in reflective thought and pragmatic inquiry is to encourage and motivate busy people to stop and reflect. That’s because most people are least interested in engaged in pragmatic inquiry when there is a real pressing doubt which requires immediate

action. And usually the larger the problem, the louder the demand for action. That’s why the quote from Abraham Lincoln’s acceptance speech to be the party candidate for Senate from Illinois, delivered at the Republican state convention, is such compelling statement. Everyone

knew that the country was in danger of being torn apart by civil war, and what is the first thing that Lincoln says: stop and reflect.

The first sentence is also a statement of logic based on his study

of Euclid: e.g. If this is true, then we would know what else is true. It is

instructive to see how he uses the same method of reflective thought

and theory to craft his most famous and memorable statements such as “House Divided” and his second inaugural address. So when you’re pressed for time, remember Lincoln’s words and engage in inquiry.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

1803-1882

Emerson was a major voice of the Transcendentalists, that amazing group of philosophers, writers and political activists including Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman and Margaret Fuller. He was also William James’s godfather.

As a wildly popular lecturer and essayist, most collections of his essays start out with that most individualistic essay “Self-reliance: Ne te quaesiveris extra. (Do not seek for things outside of yourself.)”

Well, not quite because, while still focusing on ourselves and “the essence of genius, the essence of virtue, the essence of life, which we call Spontaneity or Intuition”, he famously said: “We lie in the lap of immense intelligence, which makes us organs of its activity and receivers of its truth. When we discern justice, when we discern truth, we do nothing of ourselves, but allow a passage to its beams.”

Quite a difference from the individualistic “habits of the heart” which Tocqueville saw. And to see how ideas do develop in strange ways, consider that Nietzsche was taken by this philosophy, which led to a more radical individualistic direction, the ubermensch.

Frances E. Willard

1839-1898

Frances E Willard may not be well known today, but in her time, she was widely heralded as the second-best known woman in the world, after Queen Victoria of England. She has unfortunately been too closely tied to the ultimately failed alcohol prohibition movement and her leadership of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. However, she was early awakened to the rights of women – first woman president of a US college, Evanston College for Ladies (later a dean at Northwestern) – and that was her cause: “By nature I am progressive in my thought. Dedicating my life to the uplift of humanity, I have entered the lists at the first open place I found and have fought on as best I could…”

Later in life she called for work guided by “Scientific Philanthropy: we are learning that this is not a cold and heartless phrase, but one warmed and vivified by the very breath of God… We are all by nature narrow… But the modern scientific method is to study the correlations of each subject taken up, and it is of equal importance in the scientific study of reforms as opposed to the helter-skelter method which they have been too often pursued.” One of her most influential works was entitled: Do Everything, stating her interdisciplinary/holistic approach to social reform. Couldn’t be a better statement of Pragmatic Inquiry involving all stakeholders, the “Beloved Community” of Royce.

While she never used the term pragmatism, she was prophetic in announcing that reflecting on her lifetime of work had made her a “Gospel Socialist”, a perfect statement of reflecting on the evidence of values in action. She went on to say that: “It will take several generations to change the set of brain and trend of thought so that in place of an individual we shall have a corporate conscience.” Think about the debate we are having today about “socialism.” Her definition is still instructive: “The world owes no man a living, But it does owe him the work by which he may live in a helpful and honorable fashion.” How much pragmatic work our generation and future ones still have to do.